The optimistic inventor

Dan Gelbart, Weizmann-identified whiz kid, recalls a storied career

Features

“I have been building things for as long as I can remember myself,” says Dan Gelbart, a German-born, Israel-raised, and―since 1973―Canada-based inventor. At the age of 16, Gelbart won the Weizmann Institute’s first-ever physics competition for high school students. His prize-winning entry was an original motor he designed and built using spare parts from wherever he could get them, including from his mother’s kitchen.

“My mother, who worked as a bookkeeper, wasn’t too thrilled because she wanted me to become a doctor,” Gelbart recalls, adding that his father, on the other hand, was very encouraging. “Dad was a struggling Yiddish writer who reviewed books that no one read. Suffice it to say that he thought that my interest in electronics was terrific; his dream for me was that I would stay as far away from the arts as possible.”

Gelbart’s father took his concerns right to the gates of the Institute, accompanying his son to his first day on the job in a Weizmann lab―a three-month position that was the young inventor’s prize for winning the physics competition. During summer vacation, Gelbart was slated to work in the lab headed by Prof. Ephraim Frei, a pioneer of electronics research in Israel and a founding member of the Weizmann Institute’s Electronics Department (now the Department of Physics of Complex Systems).

“My father walked right up to Prof. Frei and asked whether a physicist could make a good living,” he recalls with a smile. “Prof. Frei answered yes, but only if the physicist is good.”

Gelbart’s father shouldn’t have worried. His son grew up to become the co-founder, in 1984, of Creo, a company based in British Columbia, Canada that developed laser-based products for the printing industry. In 2005, Creo was sold to Kodak for $1 billion. A significant portion of Creo’s award-winning technology was invented by Gelbart himself.

His extensive resume includes the co-founding of medical device companies, and the invention of numerous technologies used in the fields of optics and telecommunications. Ultimately, Gelbart would go on to register 145 patents, including one for a mobile data terminal that quickly became the best-selling device of its type in the world.

Making something from nothing

Despite his success in business, Gelbart states that he never approached the machines he built as a means of making money. Rather, he says, he was motivated by his deep-seated love of making something out of nearly nothing, an approach that he traces back to his early days in Bnei Brak.

“My parents were Holocaust survivors, and I was born in a DP [displaced persons] camp, but after being brought to Israel as a baby I had a wonderful childhood,” he says, adding that his was the first generation of Jewish youth that didn’t understand what anti-Semitism was, and that he never felt poor. “When I needed parts for the things I built, I found them in the junkyard; there was no such thing as going to the store to buy something. We had no money―no one we knew had money―but we were optimistic; we knew that life could only get better.”

And get better it did. Years of independent tinkering in his home workshop had burnished Gelbart’s natural talent for innovation, and his teachers took notice. He was given the run of his high school’s lab facilities, where he built various machines and designed experiments that were incorporated into the curriculum of his peers’ science classes. Along with his outstanding technical skills, he was recognized for his maturity; when a physics instructor would call in sick, Gelbart―a popular boy known for his sense of humor―was often asked to step in and teach the class, to the delight of all.

When Gelbart learned that the Weizmann Institute was sponsoring its first student competition, he jumped at the chance to participate.

“It was an open challenge for students to build some kind of science-related model, with no limits on the topic, or on the materials used. I decided to make a working model that would explain how an electric motor works, based on simple things we had around the house, as well as some additional materials I had to buy,” Gelbart says, recalling how he spent less than five lirot―a very modest sum in Israel’s pre-shekel currency―to get everything he needed.

His design impressed the committee of judges, which included Prof. Michael Sela, the immunology researcher who, 10 years later, would be named the Weizmann Institute’s President. Also on the committee was Prof. Frei, who would go on to supervise Gelbart in his lab over the summer. According to one of the many articles covering the competition that appeared in the local Israeli press at the time, Prof. Frei was quite struck by the boy’s work.

“We simply could not believe that a 16-year-old had built a machine of this type,” he was quoted as saying. “It was an elegant and simple design, constructed with a level of technical skill that was really remarkable.”

Prof. Frei and his colleagues interviewed Gelbart, peppering him with technical questions that confirmed that the boy had built the model entirely on his own, and that he was in full command of the relevant scientific principles.

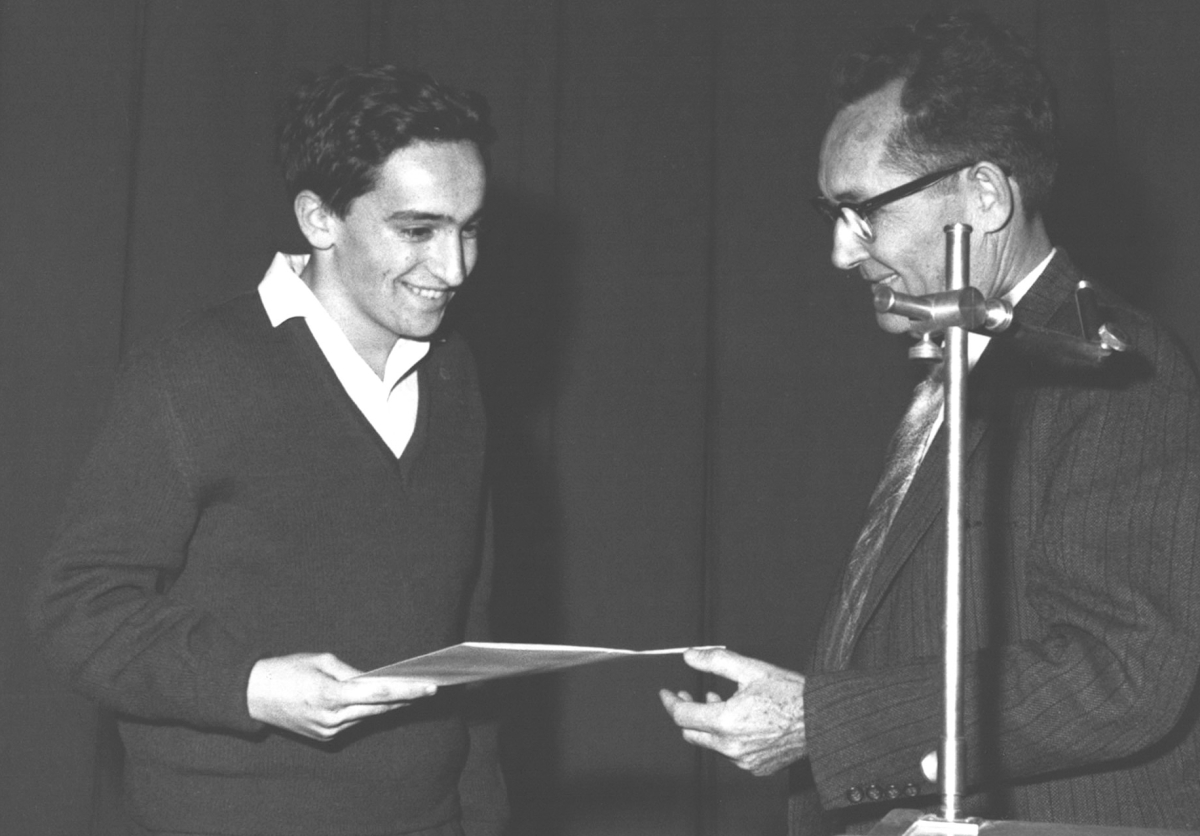

Prof. Shneor Lipson, Chair of the Scientific Council, presents Daniel Gelbart

with first prize in Weizmann's physics competition, 1963.

Online influencer

After his graduation from high school, Gelbart went to study at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and, during his third year of studies, participated as an infantry soldier in the 1967 Six Day War. Later, together with his wife, he moved to Vancouver.

Gelbart’s first job in Canada was with MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA), a company that builds machinery for the space industry. The technologies he developed there led to the founding of two additional companies―MDI-Motorola and Cymbolic Sciences―as well as the printing technology company Creo, which was eventually acquired by Kodak.

After retiring from business, Gelbart volunteered as an adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia for a number of years. Tech and innovation were the topics of his teaching as well as part and parcel of his educational approach; in addition to teaching in the classroom, Gelbart launched a highly successful YouTube channel featuring lessons filmed in his home machine shop. In these lessons, which have been viewed millions of times, Gelbart demonstrates the wide range of customized tools he uses to complete his prototypes and encourages viewers to create inventions of their own.

“I love teaching, and it seems to run in the family,” he says, noting that he and his wife have three children, and one―his son the professor―followed in his footsteps, leaving his job at university to open a science and technology high school. “But to make education interesting, there has to be a storytelling element. Maybe that’s something I inherited from my father, the writer.”

In the videos on his YouTube channel, the joy that Gelbart gets from teaching is evident, as is his delight in making ingenious and inexpensive modifications to the machines he uses for his work. He warns subscribers to his channel to think twice before investing in state-of-the-art technology.

“My electronic test equipment is a generation old, which I prefer because it’s simple to use, simple to understand, and never fails,” he says in one video, proudly pointing out a machine that he says can measure phase to a fraction of a degree and measure energy down to a microvolt. “If it breaks down, don’t worry about spare parts, just buy another one on eBay.”

Can-do spirit

When it comes to the Weizmann Institute, Gelbart says he admires its can-do spirit, and particularly the work of Yeda Research and Development, the Institute’s technology transfer company, which has contributed so much to the Israeli economy.

“When you live in Israel, you see the problems, but when you look from a distance―like my distant point of view here in Vancouver― the problems are much smaller than the achievements,” he says, adding that he was pleased to learn that Israel’s GDP per capita had surpassed that of Germany. “Science and technology play a huge part in this, of course.”

Looking back at his experience on the Weizmann Institute campus when he was in high school, Gelbart says he got a taste of the audacious inventiveness that helped write Israel’s economic success story.

“As a summer student, I remember attending a presentation given to members of the faculty by Amos de Shalit,” he says, referring to the nuclear physicist and Israel Prize laureate who was the driving force behind the Weizmann Institute’s science education program. “De Shalit told the scientists in the audience that he was leaving on a fundraising trip abroad and that, in order to raise money, he intended to exaggerate their achievements just a little bit. Then he told them that, by the time he returned to campus, he expected the scientists to make sure that what he said was no longer an exaggeration.”

The Institute continues to sponsor a range of competitions designed to identify outstanding high-school-aged scientists, something that has helped to launch many careers in academia, in tech, and even in Gelbart’s own extended family.

“Here’s a funny coincidence. I have a nephew named Zeev, who’s around my age, who also lives in Canada, and who also had a career in technology and business,” he says. “It all began when he won the Weizmann physics competition a year after I did.”